Introduction

This room is part of a series of rooms that will introduce you to reverse engineering software on Windows. This room will talk about the basics of reverse engineering. In future rooms, we will start doing some reverse engineering and work our way up in difficulty and complexity. This series will focus on analyzing executables, however, keep in mind that reversing is a large field not just covering binary analysis, and not just covering software.

What Is Reverse Engineering?

Reverse engineering is essentially being given a result and figuring out how it got there. That knowledge can be used to find vulnerabilities in the logic and methods used to achieve the result. It starts with finding what you want to attack, then figuring out how it works, then finally doing what you want with it. For security researchers, the goal of reverse engineering is to find where the developers made a mistake or got lazy. For example, developers often think encrypting network traffic is enough, but reverse engineers can get around that encryption. This is why developers shouldn’t encrypt the data their software sends to their servers, and then be lazy about sanitizing the data when it hits the server.

It’s a Long Road…

Becoming a skilled reverse engineer is quite a long process. Rest assured, once you do develop your skills it’s quite fun. No one can teach you everything you need to know about reverse engineering. You’re going to constantly see something new and it’s going to confuse you. That’s the life of a reverse engineer. It’s really frustrating for some people, but as a reverse engineer, you’re often left to figure it out yourself. You’ll constantly be looking up how something works, then tinkering around with it yourself. Keep your head up though, eventually, you can start to use your skills to find vulnerabilities, develop exploits, manipulate processes, and do loads of awesome stuff.

Why is it so hard?

Computers aren’t supposed to be human-friendly, they’re built to be fast. Think of assembly as a unionization between computer and human languages; Something the computer could understand and perform quickly, while also giving us humans something to understand (opcodes). Over time, however, that’s changed. We now almost exclusively write in high-level languages and compilers translate that into computer language. There’s a massive difference between compiler-generated assembly and human-written assembly. Compilers use all kinds of crazy techniques that sometimes don’t even make sense, but it’s for efficiency. Yes, the high-level code was originally written by a human, but the compiler has done away with the human inefficiencies. This is why it can be so hard to reverse engineer software sometimes. On the bright side, eventually, you’ll start to think more like the compiler and it won’t be as bad. You may even develop the ability to finally write good code!

Tools

This course won’t be dependent on any single tool so use what you want. x64dbg, Ghidra, and SysInternals will be provided on the VMs used in future rooms of this series.

Prerequisites (Knowledge and Notes):

- Computer Science Concepts

- You don’t need a degree, and some concepts will be covered here. Ultimately it’s your understanding of how computers and software work that will lead you to your success or failure.

- C/C++ Experience

- For reverse engineering, experience matters more than knowing advanced C/C++ techniques. Advanced techniques are almost always just abstractions of multiple simpler concepts anyways.

- Assembly (Recommended)

- I will cover the basics. You don’t need to know a ton of assembly, but being knowledgeable and comfortable with it will make you significantly better and faster. I will use the Intel syntax because I think it’s the easiest to read and it’s the default for Windows tools. Note that when working with Linux, AT&T is more commonly used.

Mindset

Something to understand is that computers are extremely stupid. They operate with pure logic and they don’t make any assumptions.

I will attempt to demonstrate this with a basic “riddle” (admittedly not a hard one).

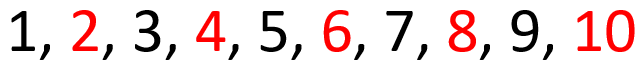

Let’s say you tell the computer to write the numbers 1-10 and make all of the even numbers red. This is what you might expect:

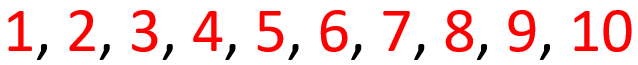

That looks correct, all even numbers are red just as expected. The computer may also generate the following:

Once again, the list is valid and follows the rules. All even numbers are red. If you’re confused, don’t worry, that means you passed the CAPTCHA. Some people’s brains will flip the rule and tell them that all red numbers are even, which is not true according to what we told the computer. Computers won’t flip the rules or apply any sort of assumptions like a human might.

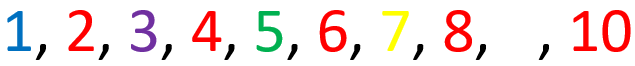

In fact, the rules don’t dictate anything about the odd numbers, so they can be any color we want!

“Where did the 9 go?”, the programmer thought. “The computer must have made an error and forgot to write the 9. Maybe I’m off by one, classic error!” And on the little programmer goes on to waste hours of his life, eventually slamming his head on the desk once he figures out it was colored white.

What is a Protocol?

TCP, UDP, HTTP(s), FTP, and SMTP are all protocols. Protocols are simply templates that are used to specify what data is where. Let’s use an example.

01011990JohnDoe/0/123MainSt

Without some sort of guide or template, that just seems like a mess of data. Our brains can pick out some information such as a name and a street. But computers can’t do that, and even we can’t pick out all of the data. It’s confusing because it’s all packed together in an attempt to make it as small as possible. Here, let me give you the secret formula:

BIRTHDAY(MMDDYYYY)NAME/NumOfChildren/HomeAddress

Now it makes sense. The collection of numbers at the start is a birthday. Following the birthday is a name. There is then a forward slash and the number of children they have. Then another forward slash and a home address. Here is another example:

03141879AlbertEinstein/3/112MercerSt

That’s what a protocol is. It’s simply a template that computers can use to pick apart a series of data that would otherwise seem pointless.

I also want to point out the delimiters (the forward slashes) used for the number of children and the street they live on. Because some data has a variable length, it’s a good idea to distinguish between them in some way besides a specific number of characters. Remember, a computer can’t make assumptions. We need to be very literal or it won’t know what we mean. The rules for the protocol are as follows: Assuming the template is filled out correctly, the first 8 characters represent the birth date. The characters following the date up to the forward-slash are the person’s name. Then the next character(s) following that forward slash and up to the next forward slash is the number of children that person had. Finally, the rest of the data after the final forward slash is the person’s home address.

Number Systems

Numbers Systems

Base 10

We mortal humans use the decimal (base 10) system. Base 10 includes 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Here is 243 in base 10: 243 = (102 * 2) + (101 * 4) + (100 * 3) = 200 + 40 + 3.

If decimal is denoted, it will usually be with the suffix of “d” such as 12d.

Base 7

We can apply this to any base. For example, 243 in base 7: 243(in base 7) = (72 * 2) + (71 * 4) + (70 * 3) = 98 + 28 + 3 = 129(in decimal).

Base 7 includes 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 9 isn’t in base 7, so how do we represent it in base 7? 9(in decimal) = (71 * 1) + (70 * 2) = 7 + 2. Our answer is going to be 12(base7) = 9(base10).

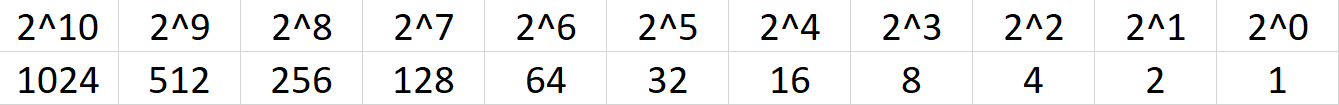

Base2/Binary

What about base 2? Base 2 includes 0 and 1. It works the same as the others. Here are some good values to know: 210 = 1024, 29 = 512, 28 = 256, 27 = 128, etc.

If you want to learn binary conversion and how to evaluate different bases, go here:

https://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra-home/alg-intro-to-algebra/algebra-alternate-number-bases/v/number-systems-introduction

Trying to explain this stuff through text can be a little difficult, but that video describes it very well.

Binary is usually denoted with the prefix “0b” such as 0b0110 and sometimes denoted with the suffix “b” such as 110b.

Hexadecimal:

Hexa = 6, Dec = 10. Hexadecimal is base 16. Hexadecimal is very similar but can be a little confusing for some people. You see, we only have ten different individual numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Hexadecimal needs 16 different numbers. You could use 0, 1… 11, 12, 13… but that would be extremely confusing. For example, what is 1432? Is that 1,4,3,2 or 14,3,2? When we need to represent anything above 9 we can instead use letters such as A, B, C, D, E, and F in the case of hexadecimal.

A = 10, B = 11, …, F = 15

Hexadecimal numbers are usually given a “0x” prefix or the suffix “h” such as 0xFF or FFh.

0x4A = (161 * 4d) + (160 * 10d) = 64d + 10d = 74d.

Learn more hexadecimal here:

https://www.khanacademy.org/math/algebra-home/alg-intro-to-algebra/algebra-alternate-number-bases/v/hexadecimal-number-system

Prefixes and Suffixes:

To distinguish between different number systems, we use prefixes or suffixes. There are many things used to distinguish between the number systems, I will only show the most common.

Decimal is represented with the suffix “d” or with nothing. Examples: 12d or 12. Hexadecimal is represented with the prefix “0x” or suffix “h”. Examples: 0x12 or 12h. Another way hexadecimal is represented is with the prefix of “\x”. However, this is typically used per byte. Two hexadecimal digits make one byte. Examples: \x12 or \x12\x45\x21. If bits and bytes seem a little weird we’ll get into them soon so don’t worry. Binary is represented with a suffix “b” or with padding of zeros at the start. Examples: 100101b or 00100101. The padding at the start is often used because a decimal number can’t start with a zero.

What is 0xA in decimal?

10

What is decimal 25 in hexadecimal? Include the prefix for hexadecimal.

0x19

Bits and Bytes

Bits and Bytes

Data type sizes vary based on architecture. These are the most common sizes and are what you will come across when working with desktop Windows and Linux.

- Bit is one binary digit. Can be 0 or 1

- Nibble is 4 bits

- Byte is 8 bits

- Word is 2 bytes

- Double Word (DWORD) is 4 bytes. Twice the size of a word

- Quad Word (QWORD) is 8 bytes. Four times the size of a word

Before we get into other data types, let’s talk about signed vs unsigned. Signed numbers can be positive or negative. Unsigned numbers can only be positive. The names come from how they work. Signed numbers need a sign bit to distinguish whether or not they’re negative, similar to how we use the + and - signs.

Data Type Sizes

- Char - 1 byte (8 bits).

- Int - There are 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit integers. When talking about integers, it’s usually 32-bit. For signed integers, one bit is used to specify whether the integer is positive or negative.

- Signed Int

- 16 bit is -32,768 to 32,767.

- 32 bit is -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647.

- 64-bit is -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807.

- Unsigned Int - Minimum is zero, maximum is twice that of a signed int (of the same size). For example: unsigned 32-bit int goes from 0 to 4,294,967,295. That is twice the signed int maximum of 2,147,483,647, however, its minimum value is 0. This is due to signed integers using the sign bit, making it unavailable to represent a value.

- Signed Int

- Bool - 1 byte. Interestingly, a bool only needs 1 bit because it’s either 1 or 0 but it still takes up a full byte. This is because computers don’t tend to work with individual bits due to alignment (talked about later). So instead, they work in chunks such as 1 byte, 2 bytes, 4 bytes, 8 bytes, and so on.

For more data types go here: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/cprogramming/c_data_types.htm

Offsets

Data positions are referenced by how far away they are from the address of the first byte of data, known as the base address (or just the address), of the variable. The distance a piece of data is from its base address is considered the offset. For example, let’s say we have some data, 12345678. Just to push the point, let’s also say each number is 2 bytes. With this information, 1 is at offset 0x0, 2 is at offset 0x2, 3 is at offset 0x4, 4 is at offset 0x6, and so on. You could reference these values with the format BaseAddress+0x##. BaseAddress+0x0 or just BaseAddress would contain the 1, BaseAddress+0x2 would be the 2, and so on.

How many bytes is a WORD?

2

How many bits is a WORD?

16

Binary Operations

This is going to be a quick introduction to how binary is manipulated and how basic mathematical operations are performed in binary. Let’s start with learning what true and false mean for a computer, then we’ll talk about the four fundamental operations: NOT, AND, OR, and XOR.

True / False

In computing, false is represented with the value 0, and true is represented as anything other than 0. This is why in binary true is 1 and false is 0. When programming true could be, 1, 100, a memory address, or a character. Again, true is anything other than 0.

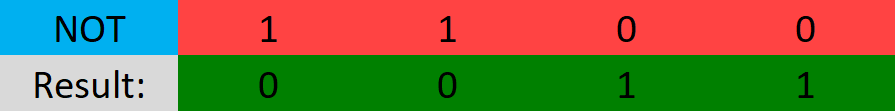

NOT (Shown as "!")

The NOT operation will simply flip the bit.

- NOT 1 = 0

- NOT 0 = 1

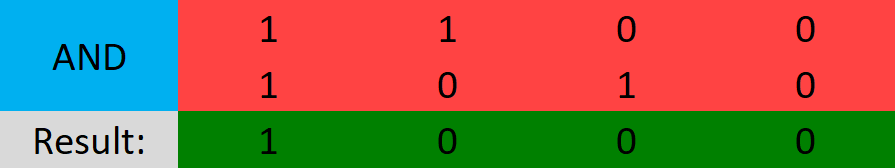

AND (Shown as "&")

AND will check if both bits are 1 and if they are the result will be 1, otherwise, the result is 0.

- 1 AND 1 = 1

- 1 AND 0 = 0

- 0 AND 0 = 0

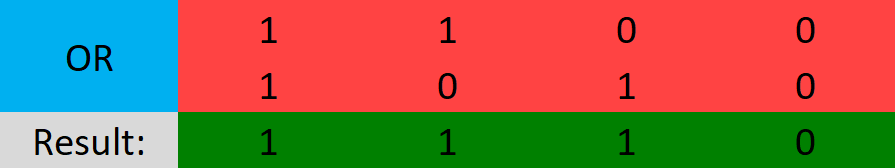

OR (Shown as "|")

OR will check if one of the bits is one and if so, then the result is 1, otherwise, the result is 0.

- 1 OR 1 = 1

- 1 OR 0 = 1

- 0 OR 0 = 0

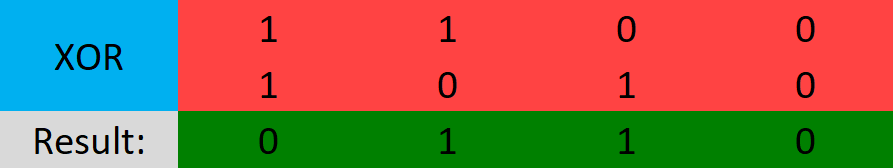

XOR (Shown as "^")

The result is 1 if either of the bits is one, but not both, otherwise, the result is 0. Another way to think of XOR is it’s checking if the bits are different.

- 1 XOR 1 = 0

- 1 XOR 0 = 1

- 0 XOR 0 = 0

There are inverses of these operations, such as NAND and NOR. These operations perform the respective primary operation then perform a NOT at the end. For example, NAND performs an AND operation followed by a NOT operation on the result of the AND operation.

What is the result of the binary operation: 1011 AND 1100?

1000

What is the result of the binary operation: 1011 NAND 1100? Include leading zeroes.

0111

Registers

Note: There are two different syntaxes for assembly: Intel and AT&T. We will focus on Intel because I think it’s the easiest to read and it’s the default for Windows tools. Note that when working with Linux, AT&T is more commonly used.

Depending on whether you are working with 64-bit or 32-bit assembly things may be a little different. As already mentioned this course focuses on 64-bit Windows.

What Is Assembly?

The end goal of a compiler is to translate high-level code into a language the CPU can understand. This language is Assembly. The CPU supports various instructions that all work together doing things such as moving data, performing comparisons, doing things based on comparisons, modifying values, and anything else that you can think of. While we may not have the high-level source code for any program, we can get the Assembly code from the executable.

Assembly VS C:

Small example:

1

2

3

4

5

if(x == 4){

func1();

}else{

return;

}

is functionally the same as the following pseudo-assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

mov RAX, x

cmp RAX, 4

jne 5 ; Line 5 (ret)

call func1

ret

This should be fairly self-explanatory, but I’ll go over it briefly. First, the variable x is moved into RAX. RAX is a register, think of it as a variable in assembly. Then, we compare that with 4. If the comparison between RAX (4) and 5 results in them not being equal then jump (jne) to line 5 which returns. Otherwise, they are equal, so call func1().

The Registers

Let’s talk about General Purpose Registers (GPR). You can think of these as variables because that’s essentially what they are. The CPU has its own storage that is extremely fast. This is great, however, space in the CPU is extremely limited. Any data that’s too big to fit in a register is stored in memory (RAM). Accessing memory is much slower for the CPU compared to accessing a register. Because of the slow speed, the CPU tries to put data in registers instead of memory if it can. If the data is too large to fit in a register, a register will hold a pointer to the data so it can be accessed.

There are 8 main general-purpose registers: There are several GPR’s, each with an assigned task. However, this task is more of a template as registers are usually used for whatever, except for a few. Regardless, it’s good to know their assigned purpose for when they are used according to their designation.

- RAX - Known as the accumulator register. Often used to store the return value of a function.

- RBX - Sometimes known as the base register, not to be confused with the base pointer. Sometimes used as a base pointer for memory access.

- RDX - Sometimes known as the data register.

- RCX - Sometimes known as the counter register. Used as a loop counter.

- RSI - Known as the source index. Used as the source pointer in string operations.

- RDI - Known as the destination index. Used as the destination pointer in string operations.

- RSP - The stack pointer. Holds the address of the top of the stack.

- RBP - The base pointer. Holds the address of the base (bottom) of the stack.

All of these registers are used for holding data. Something to point out immediately is that these registers can be used for anything. Again, their “use” is just common practice. For example, RAX is often used to hold the return value of a function but it doesn’t have to (and often doesn’t). However, imagine you were writing a program in Assembly. It would be extremely helpful to know where the return value of a function went, otherwise why call the function? Also, look at the Assembly example I gave earlier. It uses RAX to store the x variable.

With that said, some registers are best left alone when dealing with typical data. For example, RSP and RBP should almost always only be used for what they were designed for. They store the location of the current stack frame (we’ll get into the stack soon) which is very important. If you do use RBP or RSP, you’ll want to save their values so you can restore them to their original state when you are finished. As we go along, you’ll get the hang of the importance of various registers at different stages of execution.

The Instruction Pointer

RIP is probably the most important register. RIP is the “Instruction Pointer”. It is the address of the next line of code to be executed. You cannot directly write into this register, only certain instructions such as ret can influence the instruction pointer.

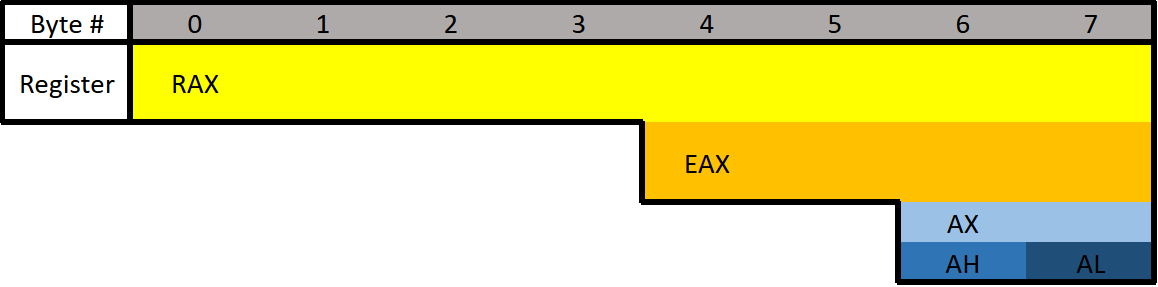

Register Break Downs

Each register can be broken down into smaller segments which can be referenced with other register names. RAX is 64 bits, the lower 32 bits can be referenced with EAX, and the lower 16 bits can be referenced with AX. AX is broken down into two 8 bit portions. The high/upper 8 bits of AX can be referenced with AH. The lower 8 bits can be referenced with AL.

RAX consists of all 8 bytes which would be bytes 0-7. EAX consists of bytes 4-7, AX consists of bytes 6-7, AH consists of only byte 6, and AL consists of only byte 7 (the final byte).

If 0x0123456789ABCDEF was loaded into a 64-bit register such as RAX, then RAX refers to 0x0123456789ABCDEF, EAX refers to 0x89ABCDEF, AX refers to 0xCDEF, AH refers to 0xCD, AL refers to 0xEF.

What is the difference between the “E” and “R” prefixes? Besides one being a 64-bit register and the other 32 bits, the “E” stands for extended. The “R” stands for register. The “R” registers were newly introduced in x64, and no, you won’t see them on 32-bit systems.

To see how all registers are broken apart go here: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/debugger/x64-architecture

Different Data Types

- Floating Point Values - Floats and Doubles.

- Integer Values - Integers, Booleans, Chars, Pointers, etc.

Different data types can’t be put in just any register. Floating-point values are represented differently than integers. Because of this, floating-point values have special registers. These registers include YMM0 to YMM15 (64-bit) and XMM0 to XMM15 (32-bit). The XMM registers are the lower half of the YMM registers, similar to how EAX is the lower 32 bits of RAX. Something unique about these registers is that they can be treated as arrays. In other words, they can hold multiple values. For example, YMM# registers are 256-bit wide each and can hold 4 64-bit values or 8 32-bit values. Similarly, the XMM# registers are 128-bits wide and can hold 2 64-bit values or 4 32-bit values. Special instructions are needed to utilize these registers as vectors.

A nice table of these registers, and more information about them, can be found here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Vector_Extensions

Extra Registers

There are additional registers that should be mentioned. These registers don’t have any special uses. There are registers r8 to r15 which are designed to be used by integer type values (not floats or doubles). The lower 4 bytes (32 bits), 2 bytes (16 bits), and 8 bits (1 byte) can all be accessed. These can be accessed by appending the letter “d”, “w”, or “b”.

Examples:

- R8 - Full 64-bit (8 bytes) register.

- R8D - Lower double word (4 bytes).

- R8W - Lower word (2 bytes).

- R8B - Lower byte.

How many bytes is RAX?

8

How many bytes is EAX?

4

Instructions

The ability to read and comprehend assembly code is vital to reverse engineering. There are roughly 1,500 instructions, however, a majority of the instructions are not commonly used or they’re just variations (such as MOV and MOVS). Just like in high-level programming, don’t hesitate to look up something you don’t know.

Before we get started there are three different terms you should know: immediate, register, and memory.

- An immediate value (or just immediate, sometimes IM) is something like the number 12. An immediate value is not a memory address or register, instead, it’s some sort of constant data.

- A register is referring to something like RAX, RBX, R12, AL, etc.

- Memory or a memory address refers to a location in memory (a memory address) such as

0x7FFF842B.

You may see a semicolon at the end of, or in-between, a few Assembly instructions. This is because the semicolon (;) is used to write a comment in Assembly.

It’s important to know the format of instructions which is as follows:

1

(Instruction/Opcode/Mnemonic) <Destination Operand>, <Source Operand>

I will be referring to Instructions/Opcodes/Mnemonics as instructions, just note that some people call it different things.

Example:

1

mov RAX, 5

MOV is the instruction, RAX is the destination operand, and 5 is the source operand. The capitalization of instructions or operands does not matter. You will see me use a mixture of all letters capitalized and all letters lowercase. In the example given, 5 is an immediate value because it’s not a valid memory address and it’s certainly not a register.

Common Instructions

Data Movement

MOV is used to move/store the source operand into the destination. The source doesn’t have to be an immediate value like it is in the following example. In the following example, the immediate value of 5 is being moved into RAX.

This is equivalent to RAX = 5.

1

mov RAX, 5

LEA is short for Load Effective Address. This is essentially the same as MOV except for addresses. They key difference between MOV and LEA is that LEA doesn’t dereference. It’s also commonly used to compute addresses. In the following example, RAX will contain the memory address/location of num1.

1

lea RAX, num1

1

lea RAX, [struct+8]

1

2

mov RBX, 5

lea RAX, [RBX+1]

In the first example, RAX is set to the address of num1. In the second, RAX is set to the address of the member in a structure which is 8 bytes from the start of the structure. This would usually be the second member. The third example RBX is set to 5, then LEA is used to set RAX to RBX + 1. RAX will be 6.

PUSH is used to push data onto the stack. Pushing refers to putting something on the top of the stack. In the following example, RAX is pushed onto the stack. Pushing will act as a copy so RAX will still contain the value it had before it was pushed. Pushing is often used to save the data inside a register by pushing it onto the stack, then later restoring it with pop.

1

push RAX

POP is used to take whatever is on the top of the stack and store it in the destination. In the following example whatever is on the top of the stack will be put into RAX.

1

pop RAX

Arithmetic

INC will increment data by one. In the following example RAX is set to 8, then incremented. RAX will be 9 by the end.

1

2

mov RAX, 8

inc RAX

DEC decrements a value. In the following example, RAX ends with a value of 7.

1

2

mov RAX, 8

dec RAX

ADD adds a source to a destination and stores the result in the destination. In the following example, 2 is moved into RAX, 3 into RBX, then they are added together. The result (5) is then stored in RAX.

Same as RAX = RAX + RBX or RAX += RBX.

1

2

3

mov RAX, 2

mov RBX, 3

add RAX, RBX

SUB subtracts a source from a destination and stores the result in the destination. In the following example, RAX will end with a value of 2.

Same as RAX = RAX - RBX or RAX -= RBX.

1

2

3

mov RAX, 5

mov RBX, 3

sub RAX, RBX

Multiplication and division are a bit different.

Because the sizes of data can vary and change greatly when multiplying and dividing, they use a concatenation of two registers to store the result. The upper half of the result is stored in RDX, and the lower half is in RAX. The total result of the operation is RDX:RAX, however, referencing just RAX is usually good enough. Furthermore, only one operand is given to the instruction. Whatever you want to multiply or divide is stored in RAX, and what you want to multiply or divide by is passed as the operand. Examples are provided in the following descriptions.

MUL (unsigned) or IMUL (signed) multiplies RAX by the operand. The result is stored in RDX:RAX. In the following example, RDX:RAX will end with a value of 125.

The following is the same as 25*5

1

2

3

mov RAX, 25

mov RBX, 5

mul RBX ; Multiplies RAX (25) with RBX (5)

After that code runs, the result is stored in RDX:RAX but in this case, and in most cases, RAX is enough.

DIV (unsigned) and **IDIV** (unsigned) work the same as MUL. What you want to divide (dividend) is stored in RAX, and what you want to divide it by (divisor) is passed as the operand. The result is stored in RDX:RAX, but once again RAX alone is usually enough.

1

2

3

mov RAX, 18

mov RBX, 3

div RBX ; Divides RAX (18) by RBX (3)

After that code executes, RAX would be 6.

Flow Control

RET is short for return. This will return execution to the function that called the currently executing function, aka the caller. As you will soon learn, one of the purposes of RAX is to hold return values. The following example sets RAX to 10 then returns. This is equivalent to return 10; in higher-level programming languages.

1

mov RAX, 10 ret

CMP compares two operands and sets the appropriate flags depending on the result. The following would set the Zero Flag (ZF) to 1 which means the comparison determined that RAX was equal to five. Flags are talked about in the next section. In short, flags are used to represent the result of a comparison, such as if the two numbers were equal or not.

1

2

mov RAX, 5

cmp RAX, 5

JCC instructions are conditional jumps that jump based on the flags that are currently set. JCC is not an instruction, rather a term used to mean the set of instructions that includes JNE, JLE, JNZ, and many more. JCC instructions are usually self-explanatory to read. JNE will jump if the comparison is not equal, and JLE jumps if less than or equal, JG jumps if greater, etc. This is the assembly version of if statements.

The following example will return if RAX isn’t equal to 5. If it is equal to 5 then it will set RBX to 10, then return.

1

2

3

4

5

mov RAX, 5

cmp RAX, 5

jne 5 ; Jump to line 5 (ret) if not equal.

mov RBX, 10

ret

NOP is short for No Operation. This instruction effectively does nothing. It’s typically used for padding because some parts of code like to be on specific boundaries such as 16-bit or 32-bit boundaries.

Back To The Example

Remember the example? Here it is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

if(x == 4){

func1();

}

else{

return;

}

is the same as

1

2

3

4

5

mov RAX, x

cmp RAX, 4

jne 5 ; Line 5 (ret)

call func1

ret

Hopefully, you can now work out the assembly version on its own. It moves the variable x into RAX, then it compares x to 4. If they are not equal then it will return, if they are equal then it calls “func1”.

Flipping Out

Remember how the compiler is all about efficiency? Let me show you how the compiler thinks, as you’re going to see it constantly.

Instead of what a programmer would typically write:

1

2

3

4

5

6

if(x == 4){

func1();

}

else{

return;

}

The compiler will generate something closer to:

1

2

3

4

5

6

if(x != 4){

goto __exit;

}

func1();

__exit:

return;

The compiler generates code this way because it’s almost always more efficient and skips more code. The above examples may not see much of a performance improvement over one another, however, in larger programs the improvement can be quite significant.

Pointers

Assembly has its ways of working with pointers and memory addresses as C/C++ does. In C/C++ you can use dereferencing to get the value inside of a memory address. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

int main(){

int num = 10;

int* ptr = &num

return (*ptr + 5);

}

ptris a pointer tonum, which meansptris holding the memory address ofnum.Then return the sum of what’s at the address inside

ptr(numwhich is 10) and 5.

Two of the most important things to know when working with pointers and addresses in Assembly are LEA and square brackets.

Square Brackets - Square brackets dereference in assembly. For example,

[var]is the address pointed to byvar. In other words, when using[var]we want to access the memory address thatvaris holding.LEA - Ignore everything about square brackets when working with LEA. LEA is short for Load Effective Address and it’s used for calculating and loading addresses.

It’s important to note that when working with the LEA instruction, square brackets do not dereference.

LEA is used to load and calculate addresses, NOT data. It doesn’t matter if there are square brackets or not, it’s dealing with addresses ONLY. LEA is the instruction that will mess with your head when you’re sleep-deprived.

Here is a simple example of dereferencing and a pointer in Assembly:

1

2

lea RAX, [var]

mov [RAX], 12

In the example above the address of var is loaded into RAX. This is LEA we are working with, there is no dereferencing. RAX is now acting as a pointer since it holds the address to the variable. Then 12 is moved into the address pointed to by RAX). The address pointed to by RAX is the var variable. If that Assembly was executed, var would be 12. This is all the same as doing mov var, 12.

Going back to the code example from when we started talking about pointers, here it is in pseudo-assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

mov num, 10

lea ptr, [num]

mov rax, [ptr]

add rax, 5

ret

Move 10 into

numLoad the address of

numintoptrMove the data that is at the address inside

ptr(numwhich is 10) intorax.Add

rax(10) and 5.RET - This will return the data inside RAX. This is explained later in calling conventions.

Earlier I said that LEA can be used to calculate addresses, and it often is, here’s an example.

1

lea RAX, [RCX+8] ;This will add 8 to the address inside RCX, and set RAX to the resulting address.

1

mov RAX, [RCX+8] ;This will add 8 to the address already held by RCX, then dereference the new address and put whatever is at that address into RAX.

One more time:

It’s important to note that when working with LEA square brackets do not dereference.

You’ll see LEA and MOV used all the time so be sure you understand this and pay attention to details.

Zero Extension

Zero extension is setting the rest of the remaining bits in a register to zero when modifying the other bits. For example, if you moved a value into EAX should the upper 32 bits of RAX change?

In general, a move to the lower 32 bits of RAX via EAX will zero out/zero extend the upper 32 bits. A move to anything less will not zero extend. So moving something into AX will not zero out the rest of RAX. If you do want to zero extend no matter what, use movzx which performs zero extension no matter what.

The JMP's Mason, what do they mean?!

Let’s talk about the difference between instructions such as jg (jump if greater) and ja (jump if above). Knowing the difference can help you snipe those hard-to-understand data types. There are other instructions like this so be sure to look up what they do when you come across them. For example, there are several variants of mov.

Here’s the rundown for the jump instructions when it comes to signed or unsigned. Ignore the “CF” and “ZF” if you don’t know what they mean, I’ve included them for reference after you understand flags (covered next).

For unsigned comparisons:

JB/JNAE (CF = 1) ; Jump if below/not above or equal

JAE/JNB (CF = 0) ; Jump if above or equal/not below

JBE/JNA (CF = 1 or ZF = 1) ; Jump if below or equal/not above

JA/JNBE (CF = 0 and ZF = 0); Jump if above/not below or equal

For signed comparisons:

JL/JNGE (SF <> OF) ; Jump if less/not greater or equal

JGE/JNL (SF = OF) ; Jump if greater or equal/not less

JLE/JNG (ZF = 1 or SF <> OF); Jump if less or equal/not greater

JG/JNLE (ZF = 0 and SF = OF); Jump if greater/not less or equal

Easy way to remember this, and how I remember it:

Humans normally work with signed numbers, and we usually say greater than or less than. That’s how I remember signed goes with the greater than and less than jumps.

Final Note

There are many more Assembly instructions that I haven’t covered. As we continue I will introduce more instructions as they come. Don’t be afraid to look up instructions, because like I said, there are quite a few (hundreds or thousands).

What instruction returns from a function?

ret

What instruction will call/execute a function?

call

What instruction could be used to save a register in a way that it can later be restored?

push

Flags

Flags are used to signify the result of the previously executed operation or comparison. For example, if two numbers are compared to each other the flags will reflect the results such as them being even. Flags are contained in a register called EFLAGS (x86) or RFLAGS (x64). I usually just refer to it as the flags register. There is an actual FLAGS register that is 16 bit, but the semantics are just a waste of time. If you want to get into that stuff, look it up, Wikipedia has a good article on it. I’ll tell you what you need to know.

Status Flags

Here are the flags you should know. Note that when I say a “flag is set” I mean the flag is set to 1 which is true/on. 0 is false/off.

- Zero Flag (ZF) - Set if the result of an operation is zero. Not set if the result of an operation is not zero.

- Carry Flag (CF) - Set if the last unsigned arithmetic operation carried (addition) or borrowed (subtraction) a bit beyond the register. It’s also set when an operation would be negative if it wasn’t for the operation being unsigned.

- Overflow Flag (OF) - Set if a signed arithmetic operation is too big for the register to contain.

- Sign Flag (SF) - Set if the result of an operation is negative.

- Adjust/Auxiliary Flag (AF) - Same as the carry flag but for Binary Coded Decimal (BCD) operations.

- Parity Flag (PF) - Set to 1 if the number of bits set in the last 8 bits is even. (10110100, PF=1; 10110101, PF=0)

- Trap Flag (TF) - Allows for single-stepping of programs.

For a full list of flags see: https://www.tech-recipes.com/rx/1239/assembly-flags/

Examples

Basic Comparison

Here are some examples to demonstrate flags being set.

Here’s the first example. The following code is trying to determine if RAX is equal to 4. Since we’re testing for equality, the ZF is going to be the most important flag. On line 2 there is a CMP instruction that is going to be testing for equality between RAX and the number 4. The way in which CMP works is by subtracting the two values. So when cmp RAX, 4 runs, 4 is subtracted from RAX (also 4). This is why the comparison results in zero because the subtraction process literally results in zero. Since the result is zero, the ZF flag is set to 1 (on/true) to denote that the operation resulted in the value of 0, also meaning the values were equal! That brings us to the JNE, which jumps if not equal/zero. Since the ZF is set it will not jump, since they are equal, and therefore the call to func1() is made. If they were not equal, the jump would be taken which would jump over the function call straight to the return.

1

2

3

4

5

6

mov RAX, 4

cmp RAX, 4

jne 5 ; Line 5 (ret)

call func1

ret

; ZF = 1, OF = 0, SF = 0

Subtraction

The following example will be demonstrating a signed operation. SF will be set to 1 because the subtraction operation results in a negative number. Using the cmp instruction instead of sub would have the same results, except the value of the operation (-6) wouldn’t be saved in any register.

1

2

3

mov RAX, 2

sub RAX, 8 ; 2 - 8 = -6.

; ZF = 0, OF = 0, SF = 1

Addition

The following is an example where the result is too big to fit into a register. Here I’m using 8-bit registers so we can work with small numbers. The biggest number that can fit in a signed 8-bit register is 128. AL is loaded with 75 then 60 is added to it. The result of adding the two together should result in 135, which exceeds the maximum. Because of this, the number wraps around and AL is going to be -121. This sets the OF because the result was too big for the register, and the SF flag is set because the result is negative. If this was an unsigned operation CF would be set.

1

2

3

mov AL, 75

add AL, 60

; ZF = 0, OF = 1, SF = 1

Final Note

Hopefully, that gives you a good idea of what flags are and how they work. Remember that CMP will set flags depending on the result of the comparison. Conditional jumps will simply look at the flags. This tells us that a conditional jump does not need to be immediately proceeded with a CMP to work. Also, flags are set by things other than CMP instructions.

If two equal values are compared to each other, what will ZF be set to as result of the comparison?

1

Calling Conventions

Windows x64 Calling Convention

There are many calling conventions, I will cover the one used on x64 Windows in detail. Once you understand one you can understand the others very easily, it’s just a matter of remembering which is which (if you choose to).

Before we start, be aware that attention to detail is very important here.

When a function is called you could, theoretically, pass parameters via registers, the stack, or even on disk. You just need to be sure that the function you are calling knows where you’re putting the parameters. This isn’t too big of a problem if you are using your own functions, but things would get messy when you start using libraries. To solve this problem we have calling conventions that define how parameters are passed to a function, who allocates space for variables, and who cleans up the stack.

Callee refers to the function being called, and the caller is the function making the call.

There are several different calling conventions including cdecl, syscall, stdcall, fastcall, and more. Because I’ve chosen to focus on x64 Windows for simplicity, we will be working with x64 fastcall. If you plan to reverse engineer on other platforms, be sure to learn their respective calling convention(s).

You will sometimes see a double underscore prefix before a calling convention’s name. For example: __fastcall. I won’t be doing this because it’s annoying to type.

Fastcall

Fastcall is the calling convention for x64 Windows. Windows uses a four-register fastcall calling convention by default. Quick FYI, when talking about calling conventions you will hear about something called the “Application Binary Interface” (ABI). The ABI defines various rules for programs such as calling conventions, parameter handling, and more.

How does the x64 Windows calling convention work?

- The first four parameters are passed in registers, LEFT to RIGHT. Parameters that are not floating-point values, such as integers, pointers, and chars, will be passed via RCX, RDX, R8, and R9 (in that order). Floating-point parameters will be passed via XMM0, XMM1, XMM2, and XMM3 (in that order).

- If there is a mix of floating-point and integer values, they will still be passed via the register that corresponds to their position. For example,

func(1, 3.14, 6, 6.28)will pass the first parameter through RCX, the second through XMM1, the third through R8, and the last through XMM3. - If the parameter being passed is too big to fit in a register then it is passed by reference (a pointer to the data in memory). Parameters can be passed via any sized corresponding register. For example, RCX, ECX, CX, CH, and CL can all be used for the first parameter. Any other parameters are pushed onto the stack, RIGHT to LEFT.

There is always going to be space allocated on the stack for 4 parameters, even if there aren’t any parameters. This space isn’t completely wasted because the compiler can, and often will, use it. Usually, if it’s a debug build, the compiler will put a copy of the parameters in the space. On release builds, the compiler will use it for temporary or local variable storage.

Here are some more rules of the calling convention:

- The base pointer (RBP) is saved when a function is called so it can be restored.

- A function’s return value is passed via RAX if it’s an integer, bool, char, etc., or XMM0 if it’s a float or double.

- Member functions have an implicit first parameter for the “this” pointer. Because it’s a pointer and it’s the first parameter, it will be passed via RCX. This can be very useful to know.

- The caller is responsible for allocating space for parameters for the callee. The caller must always allocate space for 4 parameters even if no parameters are passed.

- The registers RAX, RCX, RDX, R8, R9, R10, R11, and XMM0-XMM5 are considered volatile and must be considered destroyed on function calls.

- The registers RBX, RBP, RDI, RSI, RSP, R12, R13, R14, R15, and XMM6-XMM15 are considered nonvolatile and should be saved and restored by a function that uses them.

Stack Access

Data on the stack such as local variables and function parameters are often accessed with RBP or RSP. On x64 it’s extremely common to see RSP used instead of RBP to access parameters. Remember that the first four parameters, even though they are passed via registers, still have space reserved for them on the stack. This space is going to be 32 bytes (0x20), 8 bytes for each of the 4 registers. Remember this because at some point you will see this offset when accessing parameters passed on the stack.

- 1-4 Parameters:

- Arguments will be pushed via their respective registers, left to right. The compiler will likely use RSP+0x0 to RSP+0x18 for other purposes.

- More Than 4 Parameters:

- The first four arguments are passed via registers, left to right, and the rest are pushed onto the stack starting at offset RSP+0x20, right to left. This makes RSP+0x20 the fifth argument and RSP+0x28.

Here is a very simple example where the numbers 1 to 8 are passed from one function to another function. Notice the order they are put in.

1

function(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

MOV RCX 0x1 ; Going left to right.

MOV RDX 0x2

MOV R8 0x3

MOV R9 0x4

PUSH 0x8 ; Now going right to left.

PUSH 0x7

PUSH 0x6

PUSH 0x5

CALL function

In this case, the stack parameters should be accessed via RSP+0x20 to RSP+0x28.

Putting them in registers left to right and then pushing them on the stack right to left may not make sense, but it does once you think about it. By doing this, if you were to pop the parameters off the stack they would be in order.

1

2

3

4

POP R10 ; = 5

POP R11 ; = 6

POP R12 ; = 6

POP R13 ; = 7

Now you can access them, left to right in order: RCX, RDX, R8, R9, R10, R11, R12, R13.

Beautiful :D

Further Exploration

That’s the x64 Windows fastcall calling convention in a nutshell. Learning your first calling convention is like learning your first programming language. It seems complex and daunting at first, but that’s probably because you’re overthinking it. Furthermore, it’s typically harder to learn your first calling convention than it is your second or third.

If you want to learn more about this calling convention you can here:

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/x64-calling-convention?view=vs-2019

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/x64-software-conventions?view=vs-2019

Quick reminder, it may not hurt to go back and read the registers, memory layout, and instructions sections again. Maybe even come back and read this section after those. All of these concepts are intertwined, so it can help. I know it’s annoying and sometimes frustrating to re-read, but trust me when I say it’s worth it.

cdecl (C Declaration)

After going in-depth on fastcall, here’s a quick look at cdecl.

- The parameters are passed on the stack backward (right to left).

- The base pointer (RBP) is saved so it can be restored.

- The return value is passed via EAX.

- The caller cleans the stack. This is what makes cdecl cool. Because the caller cleans the stack, cdecl allows for a variable number of parameters.

Like I said after you understand your first calling convention learning others is pretty easy. Quick reminder, this was only a brief overview of cdecl.

See here for more info:

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/x64-software-conventions?view=vs-2019

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/x64-calling-convention?view=vs-2019

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/prolog-and-epilog?view=vs-2019

- https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/171088/x64_ABI_Intro_to_the_Windows_x64_calling_convention.php

In fastcall, what 64-bit register will hold the return value of a function?

RAX

In fastcall, what register is the first function parameter passed in?

RCX

Memory Layout

The system’s memory is organized in a specific way. This is done to make sure everything has a place to reside in.

Memory Segments

There are different segments/sections in which data or code is stored in memory. They are the following:

- Stack - Holds non-static local variables. Discussed more in-depth soon.

- Heap - Contains dynamically allocated data that can be uninitialized at first.

- .data - Contains global and static data initialized to a non-zero value.

- .bss - Contains global and static data that is uninitialized or initialized to zero.

- .text - Contains the code of the program (don’t blame me for the name, I didn’t make it).

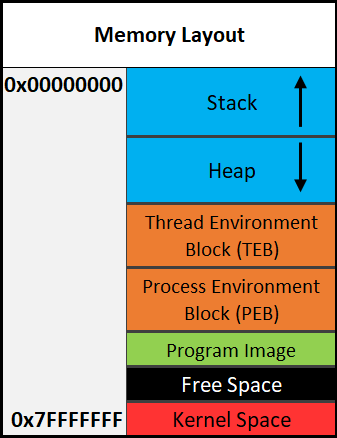

Overview of Memory Sections

Here is a general overview of how memory is laid out in Windows. This is extremely simplified.

Important:

The diagram above shows the direction variables (and any named data, even structures) are put into or taken out of memory. The actual data is put into memory differently. This is why stack diagrams vary so much. You’ll often see stack diagrams with the stack and heap growing towards each other or high memory addresses at the top. I will explain more later. The diagram I’m showing is the most relevant for reverse engineering. Low addresses being at the top is also the most realistic depiction.

Each Section Explained:

- Stack - Area in memory that can be used quickly for static data allocation. Imagine the stack with low addresses at the top and high addresses at the bottom. This is identical to a normal numerical list. Data is read and written as “last-in-first-out” (LIFO). The LIFO structure of the stack is often represented with a stack of plates. You can’t simply take out the third plate from the top, you have to take off one plate at a time to get to it. You can only access the piece of data that’s on the top of the stack, so to access other data you need to move what’s on top out of the way. When I said that the stack holds static data I’m referring to data that has a known length such as an integer. The size of an integer is defined at compile-time, the size is typically 4 bytes, so we can throw that on the stack. Unless a maximum length is specified, user input should be stored on the heap because the data has a variable size. However, the address/location of the input will probably be stored on the stack for future reference. When you put data on top of the stack you push it onto the stack. When data is pushed onto the stack, the stack grows up, towards lower memory addresses. When you remove a piece of data off the top of the stack you pop it off the stack. When data is popped off the stack, the stack shrinks down, towards higher addresses. That all may seem odd but remember, it’s like a normal numerical list where 1, the lower number, is at the top. 10, the higher number, is at the bottom. Two registers are used to keep track of the stack. The stack pointer (RSP/ESP/SP) is used to keep track of the top of the stack and the base pointer (RBP/EBP/BP) is used to keep track of the base/bottom of the stack. This means that when data is pushed onto the stack, the stack pointer is decreased since the stack grew up towards lower addresses. Likewise, the stack pointer increases when data is popped off the stack. The base pointer has no reason to change when we push or pop something to/from the stack. We’ll talk about both the stack pointer and base pointer more as time goes on.

Be warned, you will sometimes see the stack represented the other way around, but the way I’m teaching it is how you’ll see it in the real world.

- Heap - Similar to the stack but used for dynamic allocation and it’s a little slower to access. The heap is typically used for data that is dynamic (changing or unpredictable). Things such as structures and user input might be stored on the heap. If the size of the data isn’t known at compile-time, it’s usually stored on the heap. When you add data to the heap it grows towards higher addresses.

- Program Image - This is the program/executable loaded into memory. On Windows, this is typically a Portable Executable (PE).

Don’t worry too much about the TEB and PEB for now. This is just a brief introduction to them.

- TEB - The Thread Environment Block (TEB) stores information about the currently running thread(s).

- PEB - The Process Environment Block (PEB) stores information about the process and the loaded modules. One piece of information the PEB contains is “BeingDebugged” which can be used to determine if the current process is being debugged. PEB Structure Layout: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/winternl/ns-winternl-peb

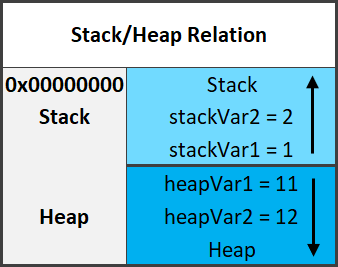

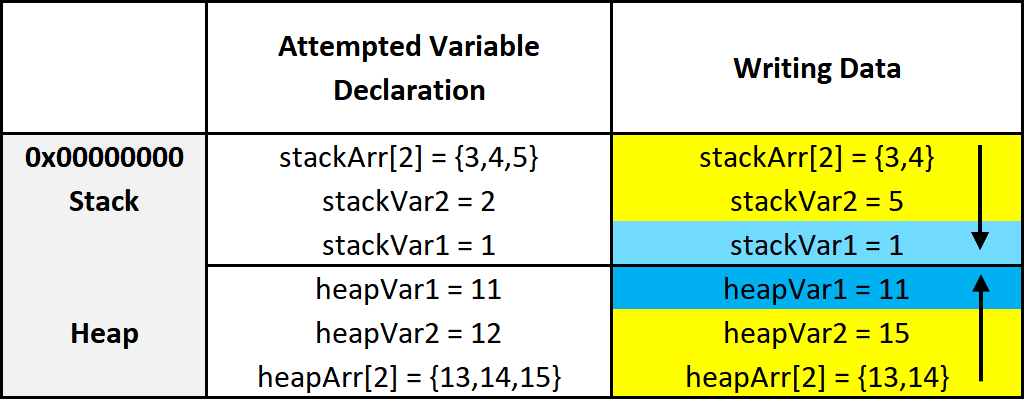

Here’s a quick example diagram of the stack and heap with some data on them.

In the diagram above, stackVar1 was created before stackVar2, likewise for the heap variables.

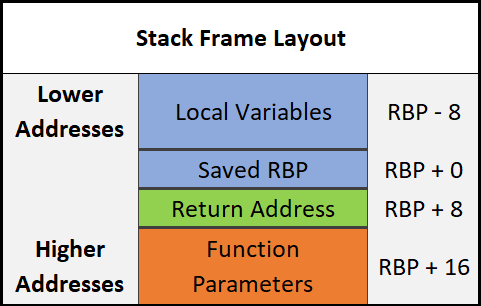

Stack Frames

Stack frames are chunks of data for functions. This data includes local variables, the saved base pointer, the return address of the caller, and function parameters. Consider the following example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int Square(int x){

return x*x;

}

int main(){

int num = 5;

Square(5);

}

In this example, the main() function is called first. When main() is called, a stack frame is created for it. The stack frame for main(), before the function call to Square(), includes the local variable num and the parameters passed to it (in this case there are no parameters passed to main). When main() calls Square() the base pointer (RBP) and the return address are both saved. Remember, the base pointer points to the base/bottom of the stack. The base pointer is saved because when a function is called, the base pointer is updated to point to the base of that function’s stack. Once the function returns, the base pointer is restored so it points to the base of the caller’s stack frame. The return address is saved so once the function returns, the program knows where to resume execution. The return address is the next instruction after the function call. So in this case the return address is the end of the main() function. That may sound confusing, hopefully, this can clear it up:

1

2

3

mov RAX, 15 ;RAX = 15

call func ;Call func. Same as func();

mov RBX, 23 ;RBX = 23. This line is saved as the return address for the function call.

I know that this can be a bit confusing but it is quite simple in how it works. It just may not be intuitive at first. It’s simply telling the computer where to go (what instruction to execute) when the function returns. You don’t want it to execute the instruction that called the function because that will cause an infinite loop. This is why the next instruction is used as the return address instead. So in the above example, RAX is set to 15, then the function called func is called. Once it returns it’s going to start executing at the return address which is the line that contains mov RBX, 23.

Here is the layout of a stack frame:

Note the location of everything. This will be helpful in the future.

Endianness

Given the value of 0xDEADBEEF, how should it be stored in memory? This has been debated for a while and still strikes arguments today. At first, it may seem intuitive to store it as it is, but when you think of it from a computer’s perspective it’s not so straightforward. Because of this, there are two ways computers can store data in memory - big-endian and little-endian.

- Big Endian - The most significant byte (far left) is stored first. This would be 0xDEADBEEF from the example.

- Little Endian - The least significant byte (far right) is stored first. This would be 0xEFBEADDE from the example.

You can learn more about endianness here.

Data Storage

As promised, I’ll explain how data is written into memory. It’s slightly different than how space is allocated for data. As a quick recap, space is allocated on the stack for variables from bottom to top, or higher addresses to lower addresses.

Data is put into this allocated space very simply. It’s just like writing English: left to right, top to bottom. The first piece of data in a variable or structure is at the lowest address in memory compared to the rest of the data. As data gets added, it’s put at a higher address further down the stack.

This diagram illustrates two things. First, how data is put into its allocated space. Second, a side effect of how data is put into its allocated memory. I’ll break down the diagram. On the left are the variables being created. On the right are the results of those variable creations. I’ll just focus on the stack for this explanation.

- On the left three variables are given values. The first variable, as previously explained, is put on the bottom. The next variable is put on top of that, and the next on top of that.

- After allocating the space for the variables, data is put into those variables. It’s all pretty simple but something interesting is going on with the array. Notice how it only allocated an array of 2 elements

stackArr[2], but it was given 3= {3,4,5}. Because data is written from lower addresses to higher or left to right and top to bottom, it overwrites the data of the variable below it. So instead ofstackVar2being 2, it’s overwritten by the 5 that was intended to be instackArr[2].

Hopefully that all makes sense. Here’s a quick recap:

Variables are allocated on the stack one on top of the other like a stack of trays. This means they’re put on the stack starting from higher addresses and going to lower addresses.

Data is put into the variables from left to right, top to bottom. That is, from lower to higher addresses.

It’s a simple concept, try not to over-complicate it just because I’ve given a long explanation. It’s vital you understand it, which is why I’ve taken so much time to explain this concept. It’s because of these concepts that there are so many depictions of memory out there that go in different directions.

RBP & RSP on x64

On x64, it’s common to see RBP used in a non-traditional way (compared to x86). Sometimes only RSP is used to point to data on the stack such as local variables and function parameters, and RBP is used for general data (similar to RAX). This will be discussed in further detail later.

In what order is data taken off of or put onto the stack? Provide the acronym.

Final Thoughts

That wraps up our introductory look at reverse engineering. You should now know a little more about low-level operations, what registers are, how assembly works, and how memory is organized. Hopefully, you enjoyed this room, however, this was one of the more boring parts of this subject so don’t fret. Getting to reverse engineer and analyze real software is where lots of fun is to be had, which is what you will learn in future rooms of this series!

One of the best ways to learn is to write your own software and reverse it to see what it looks like. I often do this when I want to learn or get familiar with a new topic. It’s especially useful when learning new methods of attack or trying exploits. It also makes you a better programmer which is nice for exploit development and more advanced reverse engineering techniques.

For further reading, the Intel and AMD (“AMD64 Architecture” section) manuals are great places to look when it comes to assembly. They contain loads of information directly from the people who made your CPU. Microsoft’s documentation (aka MSDN) is still the go-to place for developers and the documented low-level Windows concepts. Also, check out Awesome Reverse Engineering on GitHub.

Anyways, I hope to see you in the next room of this series!